Sections of the site

Editor's Choice:

- Buryat State University

- Siberian Institute of International Relations and Regional Studies (simoir): address, faculties, practice and employment

- The best books on economics and finance for beginners and professionals “Undercover Economist”, Tim Harford

- Tax received from abroad

- Choosing a university and training format

- Graphic patterns as the basis of a trading system

- Is it difficult to get into police school (College of the Ministry of Internal Affairs)

- Mindfulness: meaning, stages, lifestyle and development of the mind What does awareness mean?

- Specialist in the field of commerce and trade International commerce who to work with

- Gap year: what is it and is it possible in Russia? What do they do in gap year?

Advertising

| Five Byzantine icons worth going to the Tretyakov Gallery for. Paint an icon in the academic style at the North Athos icon painting workshop |

|

(Despite the fact that they continue to comment on the sixth chapter, and comment well, I am starting to post the seventh). Style in icon painting So, is it enough to follow - even if undisputedly, flawlessly - the iconographic canon for an image to be an icon? Or are there other criteria? For some rigorists, with light hand famous authors of the twentieth century, such a criterion is style. In everyday, philistine understanding, style is simply confused with canon. In order not to return to this issue again, we repeat once again that the iconographic canon is the purely literary, nominal side of the image : who, in what clothing, setting, action should be represented in the icon - so, theoretically, even a photograph of costumed extras in famous settings can be flawless from the point of view of iconography. Style is a system completely independent of the subject of the image. artistic vision peace , internally harmonious and unified, the prism through which the artist - and after him the viewer - looks at everything - be it a grandiose painting Last Judgment or the smallest blade of grass, a house, a rock, a person and every hair on that person's head. There is a distinction between the individual style of the artist (there are infinitely many such styles, or manners, and each of them is unique, being an expression of a unique human soul) - and style in a broader sense, expressing the spirit of an era, nation, school. In this chapter we will use the term “style” only in the second meaning. So, there is an opinion as if only those painted in the so-called “Byzantine style” are a real icon. The “academic” or “Italian” style, which in Russia was called “Fryazhsky” in the transitional era, is supposedly a rotten product of the false theology of the Western Church, and a work written in this style is supposedly not a real icon, simply not an icon at all .

This point of view is false already because the icon as a phenomenon belongs primarily to the Church, while the Church unconditionally recognizes the icon in the academic style. And it recognizes not only at the level of everyday practice, the tastes and preferences of ordinary parishioners (here, as is known, misconceptions, ingrained bad habits, and superstitions can take place). Great saints prayed in front of icons painted in the “academic” style. VIII - XX centuries, monastic workshops worked in this style, including workshops of outstanding spiritual centers such as Valaam or the monasteries of Athos. The highest hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church ordered icons from academic artists. Some of these icons, for example, the works of Viktor Vasnetsov, have remained known and loved by the people for several generations, without conflicting with the recently growing popularity of the “Byzantine” style. Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky in the 30s. called V. Vasnetsov and M. Nesterov national geniuses of icon painting, exponents of the cathedral, folk art, an outstanding phenomenon among all Christian peoples who, in his opinion, at that time had no iconography at all in the true sense of the word. Having pointed out the undoubted recognition of the non-Byzantine icon painting style by the Orthodox Church, we cannot, however, be satisfied with this. The opinion about the contrast between the “Byzantine” and “Italian” styles, about the spirituality of the first and the lack of spirituality of the second, is too widespread to not be taken into account at all. But let us note that this opinion, at first glance justified, is in fact an arbitrary fabrication. Not only the conclusion itself, but also its premises are highly questionable. These very concepts, which we put in quotation marks here for a reason, “Byzantine” and “Italian”, or academic style, are conventional and artificial concepts. The church ignores them scientific history and the theory of art also does not know such a simplified dichotomy (we hope there is no need to explain that these terms do not carry any territorial-historical content). They are used only in the context of polemics between partisans of the first and second. And here we are forced to define concepts that are essentially nonsense for us - but which, unfortunately, are firmly entrenched in the philistine consciousness. Above we have already talked about many “secondary features” of what is considered the “Byzantine style,” but the real divide between “styles,” of course, lies elsewhere. This fictitious and easily digestible opposition for semi-educated people comes down to the following primitive formula: academic style is when it “looks like” from nature (or rather, it seems to the founder of the “theology of the icon” L. Uspensky that it is similar), and Byzantine style - when it “does not look like” (according to opinion of the same Uspensky). True, the renowned “theologian of the icon” does not give definitions in such a direct form - as, indeed, in any other form. His book is generally a wonderful example of the complete absence of methodology and absolute voluntarism in terminology. There is no place at all for definitions and basic provisions in this fundamental work; conclusions are immediately laid out on the table, interspersed with preventive kicks to those who are not used to agreeing with conclusions out of nothing. So the formulas “similar - academic - unspiritual” and “dissimilar - Byzantine - spiritual” are nowhere presented by Uspensky in their charming nakedness, but are gradually presented to the reader in small digestible doses with the appearance that these are axioms signed by the fathers of the seven Ecumenical Councils- It’s not for nothing that the book itself is called - no less than - “Theology of the Icon of the Orthodox Church.” To be fair, we add that the original title of the book was more modest and was translated from French as “Theology of the Icon V Orthodox Church", this in the Russian edition the small preposition "in" disappeared somewhere, elegantly identifying Orthodox Church with a high school dropout without a theological education. But let's return to the question of style. We call the opposition between “Byzantine” and “Italian” primitive and vulgar because: a) The idea of what is similar to nature and what is not similar to it is extremely relative. Even for the same person, it can change quite dramatically over time. To bestow your own ideas about similarities with the nature of another person, and even more so of other eras and nations, is more than naive. b) In figurative fine art of any style and any era, imitation of nature does not consist in passively copying it, but in skillfully conveying its deep properties, logic and harmony visible world, subtle play and unity of correspondences that we constantly observe in Creation. c) Therefore, in psychology artistic creativity, in the viewer's assessment, resemblance to life is undoubtedly a positive phenomenon. An artist who is sound in heart and mind strives for it, the viewer expects it and recognizes it in the act of co-creation. d) An attempt at a serious theological substantiation of the depravity of similarity with nature and the blessing of dissimilarity with it would lead either to a logical dead end or to heresy. Apparently, this is why no one has made such an attempt so far. But in this work, as mentioned above, we refrain from theological analysis. We will limit ourselves to only showing the incorrectness of the division of sacred art into “fallen academic” and “spiritual Byzantine” from the point of view of history and theory of art. You don’t need to be a great specialist to notice the following: the sacred images of the first group include not only the icons of Vasnetsov and Nesterov, reviled by Uspensky, but also icons of Russian Baroque and Classicism, completely different in style, not to mention all Western European sacred painting - from the Early Renaissance to Tall, from Giotto to Durer, from Raphael to Murillo, from Rubens to Ingres. Inexpressible richness and breadth, entire eras in the history of the Christian world, rising and falling waves of great styles, national and local schools, names of great masters, about whose life, piety, mystical experience we have documentary data much richer than about “traditional” icon painters . All this endless stylistic diversity cannot be reduced to one all-encompassing and a priori negative term. And what is unhesitatingly called “Byzantine style”? Here we encounter an even cruder, even more unlawful unification under one term of almost two thousand years of history of church painting, with all the diversity of schools and manners: from the extreme, most primitive generalization of natural forms to an almost naturalistic interpretation of them, from extreme simplicity to extreme, deliberate complexity, from passionate expressiveness to the most tender tenderness, from apostolic directness to manneristic delights, from great masters of epoch-making significance to artisans and even amateurs. Knowing (from documents, and not from anyone’s arbitrary interpretations) all the heterogeneity of this huge layer Christian culture, we have no right to evaluate a priori all phenomena that fit the definition of “Byzantine style” as truly ecclesiastical and highly spiritual. And, finally, what should we do with the huge number of artistic phenomena that stylistically do not belong to one particular camp, but are located on the border between them, or, rather, at their merging? Where do we place the icons by Simon Ushakov, Kirill Ulanov and other icon painters of their circle? Iconography of the western outskirts of the Russian Empire XVI - XVII centuries?

"Joy of all who mourn" Ukraine, 17th century. St. Great Martyrs Barbara and Catherine. 18th century National Museum Ukraine Works of artists of the Cretan school XV - XVII centuries, a world-famous refuge for Orthodox craftsmen fleeing the Turkish conquerors? The phenomenon of the Cretan school alone, by its very existence, refutes all speculations opposing the fallen Western manner to the righteous Eastern one. The Cretans carried out the orders of the Orthodox and Catholics. For both, depending on the condition,in manieragreeca or in maniera latina. Often they had, in addition to a workshop in Candia, another one in Venice; Italian artists came from Venice to Crete - their names can be found in the guild registers of Candia. The same masters mastered both styles and could work alternately in one or the other, like, for example, Andreas Pavias, who painted “Greek” and “Latin” icons with equal success in the same years. It happened that compositions in both styles were placed on the doors of the same fold - this is what Nikolaos Ritsos and the artists of his circle did. It happened that a Greek master developed his own special style, synthesizing “Greek” and “Latin” characteristics, like Nikolaos Zafouris. Leaving Crete for Orthodox monasteries, Kandiot masters perfected themselves in the Greek tradition (Theofanis Strelitsas, author of icons and wall paintings of Meteora and the Great Lavra on Athos). Moving to the countries of Western Europe, they worked with no less success in the Latin tradition, nevertheless continuing to recognize themselves as Orthodox, Greeks, Candiots - and even indicate this in the signatures on their works. The most striking example is Domenikos Theotokopoulos, later called El Greco. His icons, painted in Crete, undeniably satisfy the most stringent requirements of the “Byzantine” style, traditional materials and technology, and iconographic canonicity. His paintings from the Spanish period are known to everyone, and their stylistic affiliation with the Western European school is also undoubted. But Master Domenikos himself did not make any essential distinction between the two. He always signed in Greek, he preserved the typically Greek way of working from samples and surprised Spanish customers by presenting them - to simplify negotiations - with a kind of homemade iconographic original, standard compositions of the most common subjects he had developed. In the special geographical and political conditions of the existence of the Cretan school, it always manifested itself in a particularly bright and concentrated form. the inherent unity of Christian art in the main - and mutual interest, mutual enrichment of schools and cultures . Attempts by obscurantists to interpret such phenomena as theological and moral decadence, as something originally unusual for Russian icon painting, are untenable from either theological or historical-cultural points of view. Russia has never been an exception to this rule, and it was precisely to the abundance and freedom of contacts that it owed the flourishing of national icon painting. But then what about the famous controversy? XVII V. about icon painting styles? What, then, about the division of Russian church art into two branches: “spirit-bearing traditional” and “fallen Italianizing”? We cannot turn a blind eye to these all-too-famous (and too-well-understood)phenomena. We will talk about them - but, unlike popular icon theologians in Western Europe, we will not attribute to these phenomena the spiritual meaning which they don't have. The “style debate” took place in difficult political conditions and against the background church schism. The clear contrast between the refined works of centuries-old polished national style and the first awkward attempts to master the “Italian” style gave the ideologists of “holy antiquity” a powerful weapon, which they were not slow to use. The fact that traditional icon painting XVII V. no longer possessed strength and vitality XV century, and, becoming more and more frozen, deviating into detail and embellishment, marched towards the Baroque in its own way, they preferred not to notice. All their arrows are directed against “lifelikeness” - this term, coined by Archpriest Avvakum, is, by the way, extremely inconvenient for its opponents, suggesting as the opposite a kind of “deathlikeness”. St. Righteous Grand Duke George Solovki, second quarter of the 17th century. Nevyansk, beginning 18th century

Shuya Icon of the Mother of God We will not quote in our summary the arguments of both sides, not always logical and theologically justified. We will not subject it to analysis - especially since such works already exist. But we should still remember that since we do not take the theology of the Russian schism seriously, we are in no way obliged to see the indisputable truth in the schismatic “theology of the icon.” And even more so, we are not obliged to see the indisputable truth in the superficial, biased and divorced from Russian cultural fabrications about the icon, which are still widespread in Western Europe. Those who like to repeat easily digestible incantations about the “spiritual Byzantine” and “fallen academic” styles would do well to read the works of true professionals who lived their entire lives in Russia, through whose hands thousands of ancient icons passed - F. I. Buslaev, N. V. Pokrovsky, N. P. Kondakova. All of them saw the conflict between the “old manner” and “livelikeness” much more deeply and soberly, and were not at all partisans of Avvakum and Ivan Pleshkovich, with their “gross split and ignorant Old Belief”. All of them stood for artistry, professionalism and beauty in icon painting and denounced carrion, cheap handicrafts, stupidity and obscurantism, even if in the purest “Byzantine style”. The objectives of our research do not allow us to dwell on the controversy for long XVII V. between representatives and ideologists of two directions in Russian church art. Let us turn rather to the fruits of these directions. One of them did not impose any stylistic restrictions on artists and self-regulated through orders and subsequent recognition or non-recognition of icons by the clergy and laity, the other, conservative, for the first time in history tried to prescribe an artistic style to icon painters, the subtlest, deeply personal instrument of knowledge of God and the created world. Sacred art of the first, main direction, being closely connected with life and culture Orthodox people, underwent a certain period of reorientation and, having somewhat changed technical techniques, ideas about convention and realism, the system of spatial constructions, continued in its best representatives the sacred mission of knowledge of God in images. The knowledge of God is truly honest and responsible, not allowing the artist’s personality to hide under the mask of an external style. And what happened at this time, from the end XVII to XX c., with “traditional” icon painting? We put this word in quotation marks because in reality this phenomenon not at all traditional, but unprecedented: until now, the icon painting style was at the same time a historical style, a living expression of the spiritual essence of the era and nation, and only now one of these styles has frozen into immobility and declared itself the only true one.

Nevyansk, 1894 This replacement of a living effort to communicate with God by an irresponsible repetition of well-known formulas significantly lowered the level of icon painting in the “traditional manner.” The average “traditional” icon of this period, in its artistic and spiritual-expressive qualities, is significantly lower not only than icons of earlier eras, but also contemporary icons painted in an academic manner - due to the fact that any even talented artist sought to master the academic manner , seeing in it a perfect instrument for understanding the visible and invisible world, and in Byzantine techniques - only boredom and barbarism. And we cannot but recognize this understanding of things as healthy and correct, since this boredom and barbarism were indeed inherent in the “Byzantine style”, which had degenerated in the hands of artisans, and were its late, shameful contribution to the church treasury. It is very significant that those very few masters high class who were able to “find themselves” in this historically dead style did not work for the Church. The clients of such icon painters (usually Old Believers) were for the most part not monasteries or parish churches, but individual amateur collectors. Thus, the very purpose of the icon for communication with God and knowledge of God became secondary: in best case scenario such a masterfully painted icon became an object of admiration, or, at worst, an object of investment and acquisition. This blasphemous substitution distorted the meaning and specificity of the work of the “old-fashioned” icon painters. Let us note this significant term with a clear flavor of artificiality and counterfeit. Creative work, which was once a deeply personal service to the Lord in the Church and for the Church, has undergone degeneration, even to the point of outright sinfulness: from a talented imitator to a talented forger is one step. Let us recall the classic story by N. A. Leskov “The Sealed Angel.” Famous master, at the cost of so much effort and sacrifice, found by the Old Believer community, who value their sacred art so highly. who flatly refuses to dirty his hands with a secular order turns out to be, in essence, a virtuoso master of forgery. He paints an icon with a light heart, not in order to consecrate it and place it in a church for prayer, but then, by using cunning techniques to cover the painting with cracks, wiping it with oily mud, to turn it into an object for substitution. Even if Leskov’s heroes were not ordinary swindlers, they only wanted to return the image unjustly seized by the police - is it possible to assume that the virtuoso dexterity of this imitator of antiquity was acquired by him exclusively in the sphere of such “righteous fraud”? And what about the Moscow masters from the same story, selling icons of marvelous “antique” work to gullible provincials? Under the layer of the most delicate colors of these icons, demons are discovered drawn on gesso, and cynically deceived provincials throw away the “hell-like” image in tears... The next day the scammers will restore it and sell it again to another victim who is ready to pay any money for the “true” one, i.e. -an ancient written icon... This is the sad but inevitable fate of a style that is not connected with the personal spiritual and creative experience of the icon painter, a style divorced from the aesthetics and culture of its time. Due to cultural tradition, we call not only works of art icons medieval masters, for whom their style was not stylization, but a worldview. We call icons both cheap images thoughtlessly stamped by mediocre artisans (monks and laymen), and the works of “old-timers” that are brilliant in their performing technique. XVIII - XX centuries, sometimes originally intended by the authors as fakes. But this product does not have any preemptive right to the title of icon in the church sense of the word. Neither in relation to contemporary icons of the academic style, nor in relation to any stylistically intermediate phenomena, nor in relation to the icon painting of our days. Any attempts to dictate the artist's style for reasons extraneous to art, intellectual and theoretical considerations, are doomed to failure. Even if the sophisticated icon painters are not isolated from the medieval heritage (as was the case with the first Russian emigration), but have access to it (as, for example, in Greece). It is not enough to “discuss and decide” that the “Byzantine” icon is much holier than the non-Byzantine one or even has a monopoly on holiness - one must also be able to reproduce the style declared to be the only sacred one, but no theory will provide this. Let us give the floor to Archimandrite Cyprian (Pyzhov), an icon painter and the author of a number of unfairly forgotten articles on icon painting: “Currently in Greece there is an artificial revival of the Byzantine style, which is expressed in the mutilation of beautiful forms and lines and, in general, the stylistically developed, spiritually sublime creativity of the ancient artists of Byzantium. The modern Greek icon painter Kondoglu, with the assistance of the Synod of the Greek Church, released a number of reproductions of his production, which cannot but be recognized as mediocre imitations of the famous Greek artist Panselin... Admirers of Kondoglu and his disciples say that saints “should not look like real people” - like who are they supposed to look like?! The primitiveness of such an interpretation is very harmful to those who see and superficially understand spiritual and aesthetic beauty ancient icon painting and rejects its surrogates, offered as examples of the supposedly restored Byzantine style. Often the manifestation of enthusiasm for the “ancient style” is insincere, revealing only in its supporters pretentiousness and the inability to distinguish between genuine art and crude imitation.” Such enthusiasm for the ancient style at any cost is inherent in individuals or groups, out of unreason or for certain, usually quite earthly, considerations, The word "icon" is of Greek origin. The Orthodox Church affirms and teaches that the sacred image is a consequence of the Incarnation, is based on it and is therefore inherent in the very essence of Christianity, from which it is inseparable. Sacred Tradition The image appeared in Christian art initially. Tradition dates the creation of the first icons to apostolic times and is associated with the name of the Evangelist Luke. According to legend, he depicted not what he saw, but the appearance of the Blessed Virgin Mary with the Child of God. And the first Icon is considered to be “The Savior Not Made by Hands”.

The roots of the visual techniques of icon painting, on the one hand, are in book miniatures, from which the fine writing, airiness, and sophistication of the palette were borrowed. On the other hand, in the Fayum portrait, from which the iconographic images inherited huge eyes, a stamp of mournful detachment on their faces, and a golden background. In the Roman catacombs from the 2nd-4th centuries, works of Christian art of a symbolic or narrative nature have been preserved. The Trullo (or Fifth-Sixth) Council prohibits symbolic images of the Savior, ordering that He should be depicted only “according to human nature.” In the 8th century, the Christian Church was faced with the heresy of iconoclasm, the ideology of which completely prevailed in the state, church and cultural life. Icons continued to be created in the provinces, far from imperial and church supervision. The development of an adequate response to the iconoclasts, the adoption of the dogma of icon veneration at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) brought a deeper understanding of the icon, laying down serious theological foundations, connecting the theology of the image with Christological dogmas. The theology of the icon had a huge influence on the development of iconography and the formation of iconographic canons. Moving away from the naturalistic rendering of the sensory world, icon painting becomes more conventional, gravitating towards flatness, the image of faces is replaced by the image of faces, which reflect the physical and spiritual, the sensual and the supersensible. Hellenistic traditions are gradually being reworked and adapted to Christian concepts. The tasks of icon painting are the embodiment of the deity in a bodily image. The word “icon” itself means “image” or “image” in Greek. It was supposed to remind of the image that flashes in the mind of the person praying. This is a “bridge” between man and the divine world, a sacred object. Christian icon painters managed to complete difficult task: to convey through picturesque, material means the intangible, spiritual, ethereal. Therefore, iconographic images are characterized by extreme dematerialization of figures reduced to two-dimensional shadows of the smooth surface of a board, a golden background, a mystical environment, non-flatness and non-space, but something unsteady, flickering in the light of lamps. The golden color was perceived as divine not only by the eye, but also by the mind. Believers call it “Tabor”, because, according to the biblical legend, the transfiguration of Christ took place on Mount Tabor, where his image appeared in a blinding golden radiance. At the same time, Christ, the Virgin Mary, the apostles, and saints were really living people who had earthly features. To convey the spirituality and divinity of earthly images, a special, strictly defined type of depiction of a particular subject, called the iconographic canon, has developed in Christian art. Canonicity, like a number of other characteristics of Byzantine culture, was closely connected with the system of worldview of the Byzantines. The underlying idea of the image, the sign of essence and the principle of hierarchy required constant contemplative deepening into the same phenomena (images, signs, texts, etc.). which led to the organization of culture along stereotypical principles. The canon of fine art most fully reflects the aesthetic essence of Byzantine culture. The iconographic canon performed a number of important functions. First of all, it carried information of a utilitarian, historical and narrative nature, i.e. took on the entire burden of descriptive religious text. The iconographic scheme in this regard was practically identical to the literal meaning of the text. The canon was also recorded in special descriptions appearance Saint, physiognomic instructions had to be followed strictly. Exists Christian symbolism color, the foundations of which were developed by the Byzantine writer Dionysius the Areopagite in the 4th century. According to it, the cherry color, which combines red and violet, the beginning and end of the spectrum, means Christ himself, who is the beginning and end of all things. Blue is the color of the sky, purity. Red is divine fire, the color of the blood of Christ, in Byzantium it is the color of royalty. Green color youth, freshness, renewal. Yellow is identical to gold. White is a symbol of God, similar to Light and combines all the colors of the rainbow. Black is the innermost secrets of God. Christ is invariably depicted in a cherry tunic and a blue cloak - himation, and the Mother of God - in a dark blue tunic and cherry veil - maphoria. The canons of the image also include reverse perspective, which has vanishing points not behind, inside the image, but in the person’s eye, i.e. in front of the image. Each object, therefore, expands as it moves away, as if “unfolding” towards the viewer. The image “moves” towards the person, The architectural structure of the icon and the technology of icon painting developed in line with ideas about its purpose: to bear a sacred image. Icons were and are written on boards, most often cypress. Several boards are held together with dowels. The top of the boards is covered with gesso, a primer made with fish glue. The gesso is polished until smooth, and then an image is applied: first a drawing, and then a painting layer. In the icon there are fields, a middle-central image and an ark - a narrow strip along the perimeter of the icon. The iconographic images developed in Byzantium also strictly correspond to the canon. For the first time in three centuries of Christianity, symbolic and allegorical images were common. Christ was depicted as a lamb, an anchor, a ship, a fish, a vine, and a good shepherd. Only in the IV-VI centuries. Illustrative and symbolic iconography began to take shape, which became the structural basis of all Eastern Christian art. Different understandings of the icon in the Western and Eastern traditions ultimately led to different directions in the development of art in general: having had a tremendous influence on the art of Western Europe (especially Italy), icon painting during the Renaissance was supplanted by painting and sculpture. Icon painting developed mainly on the territory of the Byzantine Empire and countries that adopted the eastern branch of Christianity-Orthodoxy. Byzantium The iconography of the Byzantine Empire was the largest artistic phenomenon in the Eastern Christian world. Byzantine art culture not only became the ancestor of some national cultures(for example, Old Russian), but throughout its existence it influenced the iconography of other Orthodox countries: Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Rus', Georgia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt. Also influenced by Byzantium was the culture of Italy, especially Venice. Byzantine iconography and the new stylistic trends that emerged in Byzantium were of utmost importance for these countries. Pre-Iconoclastic era

Apostle Peter. Encaustic icon. 6th century Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai. The oldest icons that have survived to our time date back to the 6th century. Early icons of the 6th-7th centuries preserve the ancient painting technique - encaustic. Some works retain certain features of ancient naturalism and pictorial illusionism (for example, the icons “Christ Pantocrator” and “Apostle Peter” from the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai), while others are prone to conventionality and schematic representation (for example, the icon “Bishop Abraham” from the Dahlem Museum , Berlin, icon “Christ and Saint Mina” from the Louvre). A different, not ancient, artistic language was characteristic of the eastern regions of Byzantium - Egypt, Syria, Palestine. In their icon painting, expressiveness was initially more important than knowledge of anatomy and the ability to convey volume.

The Virgin and Child. Encaustic icon. 6th century Kyiv. Museum of Art. Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko.

Martyrs Sergius and Bacchus. Encaustic icon. 6th or 7th century. Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai. For Ravenna - the largest ensemble of early Christian and early Byzantine mosaics, preserved to this day and mosaics of the 5th century (Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Orthodox Baptistery) are characterized by lively angles of figures, naturalistic modeling of volume, and picturesque mosaic masonry. In mosaics from the late 5th century (Arian Baptistery) and 6th century (basilicasSant'Apollinare Nuovo And Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Church of San Vitale ) the figures become flat, the lines of the folds of clothes are rigid, sketchy. Poses and gestures freeze, the depth of space almost disappears. The faces lose their sharp individuality, the mosaic laying becomes strictly ordered. The reason for these changes was a targeted search for a special figurative language capable of expressing Christian teaching. Iconoclastic period The development of Christian art was interrupted by iconoclasm, which established itself as the official ideology empire since 730. This caused the destruction of icons and paintings in churches. Persecution of icon worshipers. Many icon painters emigrated to the distant ends of the Empire and neighboring countries - to Cappadocia, Crimea, Italy, and partly to the Middle East, where they continued to create icons. This struggle lasted a total of more than 100 years and is divided into two periods. The first was from 730 to 787, when the Seventh Ecumenical Council took place under Empress Irina, which restored the veneration of icons and revealed the dogma of this veneration. Although in 787, at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, iconoclasm was condemned as a heresy and the theological justification for icon veneration was formulated, the final restoration of icon veneration came only in 843. During the period of iconoclasm, instead of icons in churches, only images of the cross were used, instead of old paintings, decorative images of plants and animals were made, secular scenes were depicted, in particular, horse racing, beloved by Emperor Constantine V. Macedonian period After the final victory over the heresy of iconoclasm in 843, the creation of paintings and icons for the temples of Constantinople and other cities began again. From 867 to 1056, Byzantium was ruled by the Macedonian dynasty, which gave its name Macedonian "Renaissance"

Apostle Thaddeus presents to King Abgar Miraculous image Christ. Folding sash. 10th century

King Abgar receives the Image of Christ Not Made by Hands. Folding sash. 10th century The first half of the Macedonian period was characterized by increased interest in the classical ancient heritage. The works of this time are distinguished by their naturalness in the depiction of the human body, softness in the depiction of draperies, and liveliness in the faces. Vivid examples of classical art are: the mosaic of Sophia of Constantinople with the image of the Mother of God on the throne (mid-9th century), a folding icon from the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai with the image of the Apostle Thaddeus and King Abgar receiving a plate with the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands (mid-10th century). In the second half of the 10th century, icon painting retained classical features, but icon painters were looking for ways to give the images greater spirituality. Ascetic style In the first half of the 11th century, the style of Byzantine icon painting changed sharply in the direction opposite to the ancient classics. From this time, several large ensembles of monumental painting have been preserved: frescoes of the church of Panagia ton Chalkeon in Thessaloniki from 1028, mosaics of the katholikon of the monastery of Hosios Loukas in Phokis 30-40. XI century, mosaics and frescoes of Sophia of Kyiv of the same time, frescoes of Sophia of Ohrid from the middle - 3 quarters of the 11th century, mosaics of Nea Moni on the island of Chios 1042-56. and others.

Archdeacon Lavrenty. Mosaic St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv. XI century. All of the listed monuments are characterized by an extreme degree of asceticism of images. The images are completely devoid of anything temporary and changeable. The faces are devoid of any feelings or emotions; they are extremely frozen, conveying the inner composure of those depicted. For this reason, huge symmetrical eyes with a detached, motionless gaze are emphasized. The figures freeze in strictly defined poses and often acquire squat, heavy proportions. Hands and feet become heavy and rough. The modeling of clothing folds is stylized, becoming very graphic, only conditionally conveying natural forms. The light in the simulation acquires a supernatural brightness, wearing symbolic meaning Divine Light. This stylistic trend includes a double-sided icon of the Mother of God Hodegetria with a perfectly preserved image of the Great Martyr George on the reverse (XI century, in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin), as well as many book miniatures. The ascetic trend in icon painting continued to exist later, appearing in the 12th century. An example is the two icons of Our Lady Hodegetria in the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos and in the Greek Patriarchate in Istanbul. Komnenian period

Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God. Beginning of the 12th century. Constantinople. The next period in the history of Byzantine icon painting falls on the reign of the dynasties of Douk, Comneni and Angels (1059-1204). In general it is called Komninian. In the second half of the 11th century, asceticism was again replaced by By the end of the 11th century or the beginning of the 12th century the creation Vladimir icon Our Lady (Tretyakov Gallery). This is one of best images Comnenian era, undoubtedly the work of Constantinople. In 1131-32 the icon was brought to Rus', where

Saint Gregory the Wonderworker. Icon. XII century. Hermitage Museum.

Christ Pantocrator the Merciful. Mosaic icon. XII century. The mosaic icon “Christ Pantocrator the Merciful” dates back to the first half of the 12th century. State museums Dahlem in Berlin. It expresses the internal and external harmony of the image, concentration and contemplation, the Divine and human in the Savior.

Annunciation. Icon. End of the 12th century Sinai. In the second half of the 12th century, the icon “Gregory the Wonderworker” was created from the State. Hermitage. The icon is distinguished by its magnificent Constantinople script. In the image of the saint, the individual principle is especially strongly emphasized; before us is, as it were, a portrait of a philosopher. Comnenian mannerism Crucifixion of Christ with images of saints in the margins. Icon of the second half of the 12th century. Except classical direction In the icon painting of the 12th century, other trends appeared that tended to disrupt balance and harmony in the direction of greater spiritualization of the image. In some cases, this was achieved by increased expression of painting (the earliest example is the frescoes of the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi from 1164, the icons “Descent into Hell” and “Assumption” of the late 12th century from the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai). In the latest works of the 12th century, the linear stylization of the image is extremely enhanced. And the draperies of clothes and even faces are covered with a network of bright whitewash lines, which play a decisive role in constructing the form. Here, as before, light has the most important symbolic meaning. The proportions of the figures are also stylized, becoming overly elongated and thin. Stylization reaches its maximum manifestation in the so-called late Comnenian mannerism. This term primarily refers to the frescoes of the Church of St. George in Kurbinovo, as well as a number of icons, for example, the “Annunciation” of the late 12th century from the collection in Sinai. In these paintings and icons, the figures are endowed with sharp and rapid movements, the folds of clothing curl intricately, and the faces have distorted, specifically expressive features. In Russia there are also examples of this style, for example, the frescoes of the Church of St. George in Staraya Ladoga and the reverse of the icon “Savior Not Made by Hands,” which depicts the veneration of angels to the Cross (Tretyakov Gallery). XIII century The flourishing of icon painting and other arts was interrupted by the terrible tragedy of 1204. This year, the knights of the Fourth Crusade captured and terribly sacked Constantinople. For more than half a century, the Byzantine Empire existed only as three separate states with centers in Nicaea, Trebizond and Epirus. The Latin Crusader Empire was formed around Constantinople. Despite this, icon painting continued to develop. The 13th century was marked by several important stylistic phenomena. Saint Panteleimon in his life. Icon. XIII century. Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai. Christ Pantocrator. Icon from the Hilandar monastery. 1260s At the turn of the XII-XIII centuries, in the art of the entire Byzantine world there was a significant change stylistics. Conventionally, this phenomenon is called “art around 1200.” Linear stylization and expression in icon painting are replaced by calm and monumentalism. The images become large, static, with a clear silhouette and a sculptural, plastic form. A very characteristic example of this style are the frescoes in the monastery of St. John the Evangelist on the island of Patmos. A number of icons from the monastery of St. date back to the beginning of the 13th century. Catherine on Sinai: “Christ Pantocrator”, mosaic “Our Lady Hodegetria”, “Archangel Michael” from the Deesis, “St. Theodore Stratelates and Demetrius of Thessalonica." All of them exhibit features of a new direction, making them different from the images of the Comnenian style. At the same time there arose new type hagiographic icons. If earlier scenes of the life of a particular saint could be depicted in illustrated Minologies, on epistyles (long horizontal icons for altar barriers), on the doors of folding triptychs, now scenes of life (“stamps”) began to be placed along the perimeter of the middle of the icon, in which In the second half of the 13th century, classical ideals predominated in icon painting. In the icons of Christ and the Mother of God from the Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos (1260s) there is a regular, classical form, the painting is complex, nuanced and harmonious. There is no tension in the images. On the contrary, the living and concrete gaze of Christ is calm and welcoming. In these icons, Byzantine art approached the highest possible degree of proximity of the Divine to the human. In 1280-90 art continued to follow the classical orientation, but at the same time, a special monumentality, power and emphasis of techniques appeared in it. The images showed heroic pathos. However, due to excessive intensity, the harmony decreased somewhat. A striking example of icon painting from the late 13th century is “Matthew the Evangelist” from the icon gallery in Ohrid. Crusader workshops A special phenomenon in icon painting are the workshops created in the east by the crusaders. They combined the features of European (Romanesque) and Byzantine art. Here, Western artists adopted the techniques of Byzantine writing, and the Byzantines executed icons close to the tastes of the crusaders who ordered them. As a result Palaiologan period The founder of the last dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, Michael VIII Palaiologos, returned Constantinople to the hands of the Greeks in 1261. His successor on the throne was Andronikos II (reigned 1282-1328). At the court of Andronikos II, exquisite art flourished magnificently, corresponding to the chamber court culture, which was characterized by excellent education and an increased interest in ancient literature and art. Palaiologan Renaissance- this is what is commonly called a phenomenon in Byzantine art in the first quarter of the 14th century. Theodore Stratilates» in the State Assembly meeting. The images on such icons are unusually beautiful and amaze with the miniature nature of the work. The images are either calm, Many icons painted in the usual tempera technique have also survived. They are all different, the images are never repeated, reflecting different qualities and states. So in the icon “Our Lady of Psychosostria (Soul Savior)” from Ohridhardness and strength are expressed in the icon “Our Lady Hodegetria” from the Byzantine Museum in Thessalonica on the contrary, lyricism and tenderness are conveyed. On the back of “Our Lady of Psychosostria” the “Annunciation” is depicted, and on the paired icon of the Savior on the back is written “The Crucifixion of Christ”, which poignantly conveys pain and sorrow overcome by the power of the spirit. Another masterpiece of the era is the icon “The Twelve Apostles” from the collectionMuseum of Fine Arts. Pushkin. In it, the images of the apostles are endowed with such a bright individuality that it seems that we are looking at a portrait of scientists, philosophers, historians, poets, philologists, and humanists who lived in those years at the imperial court. All of these icons are characterized by impeccable proportions, flexible movements, imposing poses of figures, stable poses and easy-to-read, precise compositions. There is a moment of entertainment, concreteness of the situation and the presence of the characters in space, their communication. Similar features were also clearly manifested in monumental painting. But here the Paleologian era brought especially Varlaam, who came to Constantinople from Calabria in Italy, and Gregory Palama- scientist-monk with Athos . Varlaam was raised in a European environment and differed significantly from Gregory Palamas and the Athonite monks in matters of spiritual life and prayer. They fundamentally differently understood the tasks and capabilities of man in communication with God. Varlaam adhered to the side of humanism and denied the possibility of any mystical connection between man and God . Therefore, he denied the practice that existed on Athos hesychasm - the ancient Eastern Christian tradition of prayer. Athonite monks believed that when they prayed, they saw the Divine light - that Source not specified During the existence of the Byzantine state, the period of which was the 4th-15th centuries, the cultural worldview of society managed to transform significantly, thanks to the emergence of new creative views and trends in art. Their unique diversity of artistic works, which differently reflected the current reality in the world, contributed to the inevitable development of the highest spiritual values, encouraging new generations of society to the greatest enlightenment. Among the most widespread types of cultural property of the Roman Empire, Special attention should be given to icon painting. History of Byzantine iconsThis is an ancient religious genre of medieval painting, where the authors had to visually illustrate images of mythical characters taken from the Bible. Images of sacred persons, which Roman artists were able to fully display on a solid surface, began to be called an icon. The creation of the first Byzantine icons was based on an ancient writing technique that gained wide popularity in ancient times. It was called encaustic. In the process of using it, icon painters had to dilute their paints by mixing them with wax, which was the main active ingredient. Its unique formula, covering the outer side of the sacred canvas, allowed the icon to retain its original appearance in its original original form for a long time. In addition, the main facial features that reflect the true view of religious personalities were presented by artistic creators very superficially, with a lack of precise detail. That is why in the first works, the Pre-Iconoclastic period, covering the period of the 6th - 7th centuries, one can immediately draw attention to the rough and in some places blurred facial features. Among their main works are Sinai icon Apostle Peter. Further, with the advent of the Iconoclastic period, the traditional creation of religious icons turned out to be extremely difficult. First of all, this was due to new socio-political movements that were actively undertaken in Byzantium for several hundred years. Ardent opponents of religious culture sought to completely ban the centuries-old veneration of icons, through their complete destruction. However, Byzantine icons nevertheless, they continued to create, carrying out this process in strict secrecy from government supervision. At that point in time, the current icon painters decided to completely change the previously established attitude towards understanding the church faith. Symbolism and images of the Byzantine iconThe new artistic concept contributed to the final change in the previous symbolism, which was marked by a transition from the old naturalistic perception of the sensory world to a more religious and sacred reflection of it. Now the images of Byzantine icons adhere to other handwritten canons. In them, ordinary human faces replaced by faces, around which a golden halo shone in a semicircular shape. Depending on the degree of holiness of the heroes who are presented in biblical mythology, the name of their faces began to be divided into categories such as Apostles; Unmercenary; The faithful; Great Martyrs; Martyrs, etc. There are 18 species in total. A clear example demonstrating the application of new artistic canons is the icon of Jesus Christ in the Byzantine style, which is called Christ Pantocrator.

Its creation was based on new color forms, which are a combination of natural and powder paints mixed in liquid. The main facial features that the artist managed to give to this shrine turned out to be so natural and correctly conveyed that in other subsequent works, God’s gaze began to be presented in exactly the same form that preceded the previously created original. The meaning of the iconsIN hard times mass famine, plague epidemic and popular uprisings, when the life and health of people were in serious danger, the significance of Byzantine shrines was extremely great in providing assistance and salvation. Their miraculous properties made it possible to heal young children and adults from many cardiovascular and headache diseases. In addition, people tried to contact them in advance, in order to create well-being for their family and friends. Influence on Old Russian iconographyThe icons of Byzantium, in all their aesthetic splendor, managed to make an invaluable contribution to the development of ancient Russian iconography. Since the main founders of cultural and religious education, first of all, it is the Roman icon painters who should be singled out. They managed to pass on their accumulated knowledge on creating church splendor not only to their future generation, but also to other states that existed at that time, one of which was Ancient Rus'. Icons of academic writing became widespread in our country at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. To be more precise, in the 18th century a steady and growing demand began to be observed, and by the 19th century this demand reached its peak. In order to order an academic icon in our workshop, just go to the Contacts section and contact the artist in the most convenient way for you: by mail, by phone. Supporters and opponents of the academic style of icon paintingIn short, opponents of academic icon painting accuse its supporters of excessive sensuality and naturalistic writing. They say it smacks of Catholicism and such icons emanate passion. Academic icon painters respond to this with the following arguments:

What style of icon painting is the most correct?Conversations around the issues of the “correctness” of styles, their “spirituality” and “canonicity” do not subside. The correctness of style is a conditional thing. It depends, first of all, on the canons of icon painting. The canons determine a lot, but not everything. A lot also depends on the culture and skill of the icon painter. For others, even academic writing does not distract from prayer and contemplation. Such icons cannot be called passionate. And for others, even the most symbolic Byzantine letter evokes nothing but regret and boredom. Such icons do not “breathe”. Craftsmen often call them “boards” or “crafts”. Of course important aspect is also the taste of the customer. If his soul lies in the direction of the academic style of writing, then the icon painter must feel this and bring it to life. Otherwise, it may turn out that the icon is good, but the customer does not understand it, does not feel it. In other words, the style of the icon is not so important as its quality and the readiness of the prayer book, the one who will pray in front of it. How much more difficult are icons of academic writing to execute?This is wrong. It is always difficult to paint an icon. It’s just that in one style some things are more difficult and painstaking, in another style others are different. If we talk about icons of the initial and intermediate levels, then a novice icon painter will probably find it easier to create more symbolic images.

However, such icons often contain complex ornaments and other decorative elements. It is in them that the mastery of execution is revealed. It may seem that the icons of the academic style are closer to painting, but this is only at first glance. Most of the image techniques and technological nuances are also described in detail. It’s just that in both cases, skill is needed. A good icon painter simply must master all the main styles of icon painting. Academic is no exception. Another question is what different masters Some things may turn out better, some things may turn out worse. As they say, what your hand is full of, and what your soul lies in. When ordering an icon of the academic style, it would be a good idea to check with the icon painter how well he knows this style, and also ask to show the work already completed. The exhibition “Masterpieces of Byzantium” is a great and rare event that cannot be missed. For the first time, a whole collection of Byzantine icons was brought to Moscow. This is especially valuable because it is not so easy to get a serious idea of Byzantine icon painting from several works located in the Pushkin Museum. It is well known that all ancient Russian icon painting came out of the Byzantine tradition, that many Byzantine artists worked in Rus'. There are still disputes about many pre-Mongol icons about who painted them - Greek icon painters who worked in Rus', or their talented Russian students. Many people know that at the same time as Andrei Rublev, the Byzantine icon painter Theophanes the Greek worked as his senior colleague and probably teacher. And he, apparently, was by no means the only one of the great Greek artists who worked in Rus' at the turn of the 14th-15th centuries. And therefore, for us, the Byzantine icon is practically indistinguishable from the Russian one. Unfortunately, science never developed precise formal criteria for determining “Russianness” when we talk about art until the middle of the 15th century. But this difference exists, and you can see this with your own eyes at the exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery, because several real masterpieces of Greek icon painting came to us from the Athens “Byzantine and Christian Museum” and some other collections. I would like to once again thank the people who organized this exhibition, and first of all the initiator and curator of the project, researcher Tretyakov Gallery Elena Mikhailovna Saenkova, head of the department of ancient Russian art Natalya Nikolaevna Sharedega, and the entire department of ancient Russian art, which took an active part in the preparation of this unique exhibition. Raising of Lazarus (12th century)The earliest icon on display. Small in size, located in the center of the hall in a display case. The icon is a part of a tyabl (or epistilium) - a painted wooden beam or large board, which in the Byzantine tradition was placed on the ceiling of marble altar barriers. These chapels were the basis of the future high iconostasis, which arose at the turn of the 14th-15th centuries. In the 12th century, the 12 great holidays (the so-called Dodekaorton) were usually written on the epistyle, and the Deesis was often placed in the center. The icon that we see at the exhibition is a fragment of such an epistyle with one scene of “The Raising of Lazarus.” It is valuable that we know where this epistyle comes from – from Mount Athos. Apparently, in the 19th century it was sawn into pieces, which ended up in completely different places. Behind last years researchers were able to discover several parts of it.

The Raising of Lazarus. XII century. Wood, tempera. Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens The Raising of Lazarus is in the Athens Byzantine Museum. Another part, with the image of the Transfiguration of the Lord, ended up in the State Hermitage, the third - with the scene of the Last Supper - is located in the Vatopedi monastery on Athos. The icon, being not a Constantinople or metropolitan work, demonstrates the highest level that Byzantine icon painting reached in the 12th century. Judging by the style, the icon dates back to the first half of this century and, with a high probability, was painted on Mount Athos itself for monastic needs. In painting we do not see gold, which has always been an expensive material.

So here we have one of the earliest examples of red-background Byzantine icons - the origins of a tradition that developed in Rus' in the 13th-14th centuries. Virgin and Child (early 13th century)This icon is interesting not only for its stylistic decision, which does not quite fit into the purely Byzantine tradition. It is believed that the icon was painted in Cyprus, but perhaps an Italian master took part in its creation. Stylistically, it is very similar to the icons of Southern Italy, which for centuries was in the orbit of the political, cultural and religious influence of Byzantium.

However, Cypriot origin cannot be ruled out either, because at the beginning of the 13th century, completely different stylistic styles existed in Cyprus, and Western masters also worked alongside the Greek ones. It is quite possible that the special style of this icon is the result of interaction and a peculiar Western influence, which is expressed, first of all, in the violation of the natural plasticity of the figure, which the Greeks usually did not allow, and the deliberate expression of the design, as well as decorative details. The iconography of this icon is curious. The Baby is shown wearing a blue and white long shirt with wide stripes that run from the shoulders to the edges, while the Baby's legs are bare. The long shirt is covered with a strange cloak, more like a drapery. According to the author of the icon, before us is a kind of shroud in which the body of the Child is wrapped. In my opinion, these robes have a symbolic meaning and are associated with the theme of the priesthood. The Child Christ is also represented as a High Priest. Associated with this idea are wide clavicle stripes running from the shoulder to the bottom edge - an important distinctive feature bishop's surplice. The combination of blue-white and gold-bearing clothes is apparently related to the theme of the coverings on the altar throne. As you know, the Throne in both the Byzantine church and the Russian one has two main covers. The lower garment is a shroud, a linen cover, which is placed on the Throne, and on top is laid out precious indium, often made of precious fabric, decorated with gold embroidery, symbolizing heavenly glory and royal dignity. In Byzantine liturgical interpretations, in particular, in the famous interpretations of Simeon of Thessaloniki at the beginning of the 15th century, we encounter precisely this understanding of two veils: the funeral Shroud and the robes of the heavenly Lord. Another very characteristic detail of this iconography is that the Baby’s legs are bare to the knees and the Mother of God is pressing His right heel with her hand. This emphasis on the heel of the Child is present in a number of Theotokos iconographies and is associated with the theme of Sacrifice and the Eucharist. We see here a echo with the theme of the 23rd Psalm and the so-called Edenic promise that the woman’s son will bruise the tempter’s head, and the tempter himself will bruise this son’s heel (see Gen. 3:15).

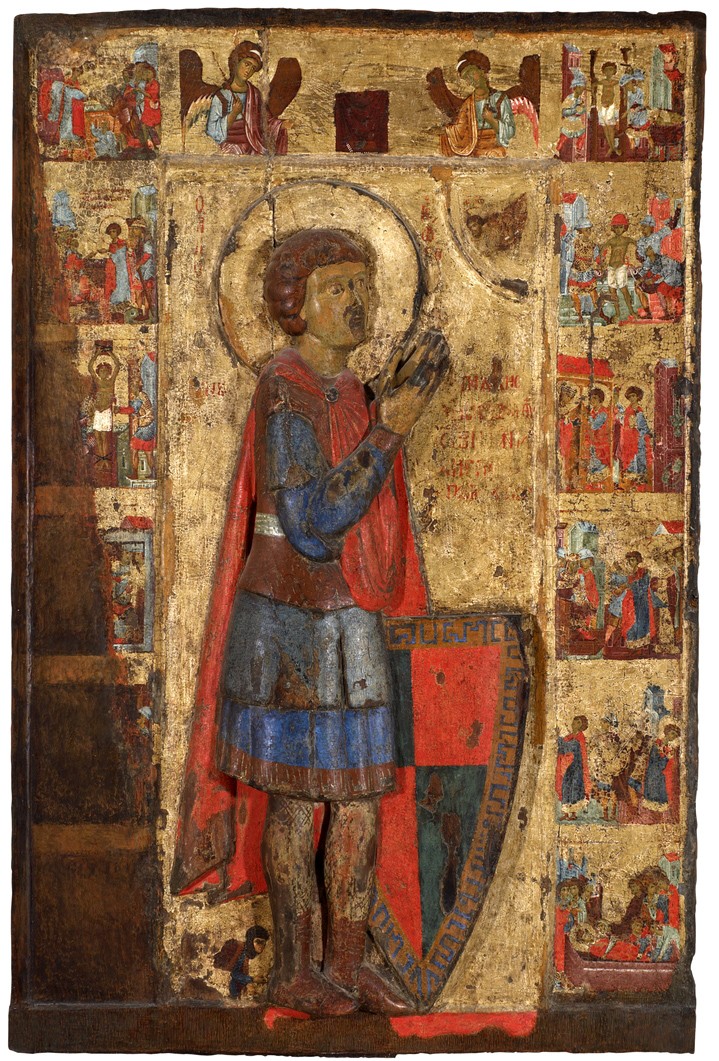

Relief icon of St. George (mid-13th century)Relief icons, which are unusual for us, are well known in Byzantium. By the way, Saint George was often depicted in relief. Byzantine icons were made of gold and silver, and there were quite a lot of them (we know about this from the inventories of Byzantine monasteries that have come down to us). Several of these remarkable icons have survived and can be seen in the treasury of St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, where they were taken as spoils of the Fourth Crusade. Wooden relief icons are an attempt to replace jewelry with more economical materials. What attracted me to wood was the possibility of the sensual tangibility of a sculptural image. Although sculpture as an icon technique was not very widespread in Byzantium, we must remember that the streets of Constantinople, before its destruction by the crusaders in the 13th century, were lined with ancient statues. And the Byzantines had sculptural images, as they say, “in their blood.”

The full-length icon shows Saint George praying, who turns to Christ, as if flying from heaven in the upper right corner of the center of this icon. In the margins is a detailed life cycle. Above the image are shown two archangels who flank the not preserved image of the “Prepared Throne (Etymasia)”. It introduces a very important time dimension into the icon, recalling the coming Second Coming.

In this icon, as in many other icons from the mid-13th century, certain Western features are visible. During this era, the main part of the Byzantine Empire was occupied by the crusaders. It can be assumed that the person who ordered the icon could have been connected with this environment. This is evidenced by the very non-Byzantine, non-Greek shield of George, which is very reminiscent of shields with the coats of arms of Western knights. The edges of the shield are surrounded by a peculiar ornament, in which it is easy to recognize an imitation of Arabic Kufic writing; in this era it was especially popular and was considered a sign of the sacred.

In the lower left part, at the feet of St. George, there is a female figurine in rich, but very strict vestments, which falls in prayer at the feet of the saint. This is the unknown customer of this icon, apparently the same name as one of the two holy women depicted on the back of the icon (one is signed with the name “Marina”, the second martyr in royal robes is an image of St. Catherine or St. Irene). Saint George is the patron saint of warriors, and taking this into account, it can be assumed that the icon commissioned by an unknown wife is a votive image with a prayer for her husband, who in this very turbulent time is fighting somewhere and needs the most direct patronage of the main warrior from the rank of martyrs. Icon of the Mother of God and Child with the Crucifixion on the back (XIV century)The most wonderful in artistically The icon of this exhibition is a large icon of the Mother of God and Child with the Crucifixion on the reverse. This is a masterpiece of Constantinople painting, most likely painted by an outstanding, one might even say, great artist in the first half of the 14th century, the heyday of the so-called “Palaeologian Renaissance”. During this era, the famous mosaics and frescoes of the Chora Monastery in Constantinople, known to many under the Turkish name Kahrie-Jami, appeared. Unfortunately, the icon suffered greatly, apparently from deliberate destruction: literally a few fragments of the image of the Mother of God and Child have survived. Unfortunately, we see mostly late additions. The crucifixion scene is much better preserved. But even here, someone purposefully destroyed the faces. But even what has survived speaks of the hand of an outstanding artist. And not just a great master, but a man of extraordinary talent who set himself special spiritual goals.

The figure of the Mother of God, wrapped in robes, was painted in lapis lazuli, a very expensive paint that was literally worth its weight in gold. Along the edge of the maforia is a golden border with long tassels. The Byzantine interpretation of this detail has not survived. However, in one of my works I suggested that it is also connected with the idea of the priesthood. Because the same tassels along the edge of the robe, also complemented by golden bells, were important feature robes of the Old Testament high priest in the Jerusalem temple. The artist very delicately recalls this internal connection of the Mother of God, who sacrifices Her Son, with the theme of the priesthood.

Mount Golgotha is shown as a small hill; behind it is visible the low city wall of Jerusalem, which on other icons is much more impressive. But here the artist seems to be showing the scene of the Crucifixion at a bird's eye level. And therefore, the wall of Jerusalem appears in the depths, and all attention, due to the chosen angle, is concentrated on the main figure of Christ and the framed figures of John the Evangelist and the Mother of God, creating the image of a sublime spatial action. The spatial component is of fundamental importance for understanding the design of the entire double-sided icon, which is usually a processional image, perceived in space and movement. The combination of two images - the Mother of God Hodegetria on one side and the Crucifixion - has its own high prototype. These same two images were on both sides of the Byzantine palladium - the icon of Hodegetria of Constantinople.

Most likely, this icon of unknown origin reproduced the theme of Hodegetria of Constantinople. It is possible that it could be connected with the main miraculous action that happened to Hodegetria of Constantinople every Tuesday, when she was taken to the square in front of the Odigon monastery, and a weekly miracle took place there - the icon began to fly in a circle in the square and rotate around its axis. We have evidence of this from many people - representatives of different nations: Latins, Spaniards, and Russians, who saw this amazing action. The two sides of the icon at the exhibition in Moscow remind us that the two sides of the Constantinople icon formed an indissoluble dual unity of the Incarnation and the Redemptive Sacrifice. Icon of Our Lady Cardiotissa (XV century)The icon was chosen by the creators of the exhibition as the central one. Here is a rare case for the Byzantine tradition when we know the name of the artist. He signed this icon, on the bottom margin it is written in Greek - “Hand of an Angel”. This is the famous Angelos Akotantos - an artist of the first half of the 15th century, of whom quite a lot remains big number icons We know more about him than about other Byzantine masters. A number of documents have survived, including his will, which he wrote in 1436. He did not need a will; he died much later, but the document was preserved. The Greek inscription on the icon “Mother of God Kardiotissa” is not a feature of the iconographic type, but rather an epithet - a characteristic of the image. I think that even a person who is not familiar with Byzantine iconography can guess what we are talking about: we all know the word cardiology. Cardiotissa – cardiac.

Icon of Our Lady Cardiotissa (XV century) Particularly interesting from the point of view of iconography is the pose of the Child, who, on the one hand, embraces the Mother of God, and on the other, seems to tip over backwards. And if the Mother of God looks at us, then the Child looks into Heaven, as if far from Her. A strange pose, which was sometimes called Leaping in the Russian tradition. That is, on the icon there seems to be a Baby playing, but He plays rather strangely and very much not like a child. It is in this pose of the overturning body that there is an indication, a transparent hint of the theme of the Descent from the Cross, and, accordingly, the suffering of the God-Man at the moment of the Crucifixion.

This icon contains the endless depth of the Byzantine tradition, but if we look closely, we will see changes that will lead to a new understanding of the icon very soon. The icon was painted in Crete, which belonged to the Venetians at that time. After the fall of Constantinople, it became the main center of icon painting throughout the Greek world. In this icon of the outstanding master Angelos, we see how he balances on the verge of turning a unique image into a kind of cliché for standard reproductions. The images of light-gaps are already becoming somewhat mechanistic; they look like a rigid grid laid on a living plastic base, something that artists of earlier times never allowed.

Icon of Our Lady Cardiotissa (XV century), fragment Before us is an outstanding image, but in in a certain sense already borderline, standing at the border of Byzantium and post-Byzantium, when living images gradually turn into cold and somewhat soulless replicas. We know what happened on Crete less than 50 years after this icon was painted. Contracts between the Venetians and the leading icon painters of the island have reached us. According to one such contract in 1499, three icon-painting workshops were to produce 700 icons of the Mother of God in 40 days. In general, it is clear that a kind of artistic industry is beginning, spiritual service through the creation of holy images is turning into a craft for the market, for which thousands of icons are painted. The beautiful icon of Angelos Akotanthos represents a striking milestone in the centuries-long process of devaluation of Byzantine values, of which we are all heirs. The more precious and important becomes the knowledge of true Byzantium, the opportunity to see it with our own eyes, which was provided to us by the unique “exhibition of masterpieces” in the Tretyakov Gallery. |

| Read: |

|---|

New

- Siberian Institute of International Relations and Regional Studies (simoir): address, faculties, practice and employment

- The best books on economics and finance for beginners and professionals “Undercover Economist”, Tim Harford

- Tax received from abroad

- Choosing a university and training format

- Graphic patterns as the basis of a trading system

- Is it difficult to get into police school (College of the Ministry of Internal Affairs)

- Mindfulness: meaning, stages, lifestyle and development of the mind What does awareness mean?

- Specialist in the field of commerce and trade International commerce who to work with

- Gap year: what is it and is it possible in Russia? What do they do in gap year?

- Specialty law enforcement who can work